Best Noir Movies You’ve Never Seen

These underseen noir gems deliver tense plots, shadowy visuals, and hard choices without the usual household names. You will find location shooting that puts you on real streets, sharp scripts that twist the knife, and directors who knew exactly where to place the camera. Many of these films were restored after years of rough prints, which makes them feel brand new. If you love moody crime stories and fatal mistakes, this list will stock your watchlist fast.

‘The Prowler’ (1951)

Joseph Losey crafts a tense story about a cop who crosses the line after a routine call. Van Heflin and Evelyn Keyes anchor a tale of obsession that spirals into fraud and murder. The film was once hard to see, then returned in a careful restoration that revealed its sleek design and crisp photography. Pay attention to how domestic spaces become traps as pressure mounts.

‘Crime Wave’ (1953)

André de Toth shoots on real Los Angeles streets for a lean story about an ex con pulled back into trouble. Sterling Hayden plays a relentless detective who treats every alibi as a lie waiting to crack. The movie moves fast with clipped dialogue and sharp daylight scenes that feel as dangerous as the nights. Its spare style turns cheap locations into vivid crime backdrops.

‘Too Late for Tears’ (1949)

Lizabeth Scott gives a fierce turn as a housewife who grabs a bag of cash and refuses to let go. Dan Duryea glides into the story with oily charm and a talent for cruelty. Long stuck in poor copies, the film gained new life through restoration that brought back its rich blacks and glittering highlights. Watch how greed poisons every conversation until trust becomes impossible.

‘Nightfall’ (1956)

Jacques Tourneur follows an ad man who stumbles into a robbery and ends up hunted across two stark landscapes. Aldo Ray and Anne Bancroft play strangers who meet by chance and try to outrun past mistakes. The film shifts between urban glare and snowy wilderness while keeping the tension tight. Tourneur uses clean compositions and quiet moments to set up sudden bursts of violence.

‘The Phenix City Story’ (1955)

Phil Karlson draws from real events in an Alabama town run by rackets and protected by fear. The movie uses a semi documentary approach with street interviews and news style scenes that feel immediate. Richard Kiley and John McIntire lead a cast that shows how civic courage meets organized retaliation. Its grit comes from tight editing and an unblinking look at local corruption.

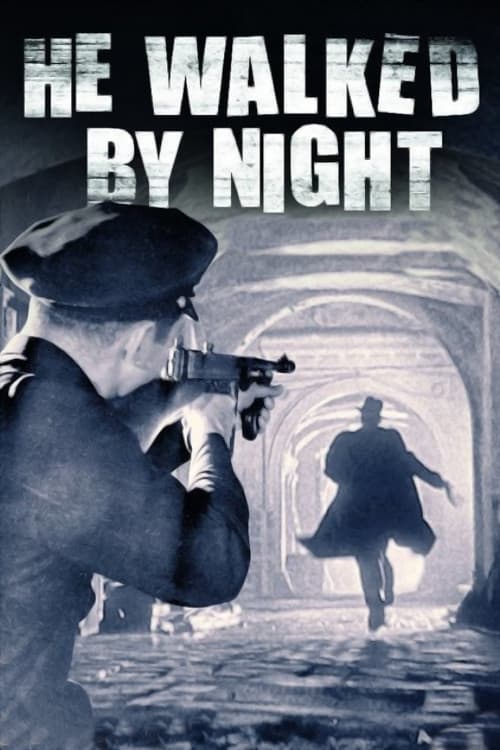

‘He Walked by Night’ (1948)

A cool headed thief turns Los Angeles into a maze as police close in step by step. Richard Basehart plays the fugitive with icy focus while investigators build a case through procedure. Anthony Mann contributed uncredited direction that sharpened the film’s tough edge. The climax races through storm drains where light and echo create unforgettable tension.

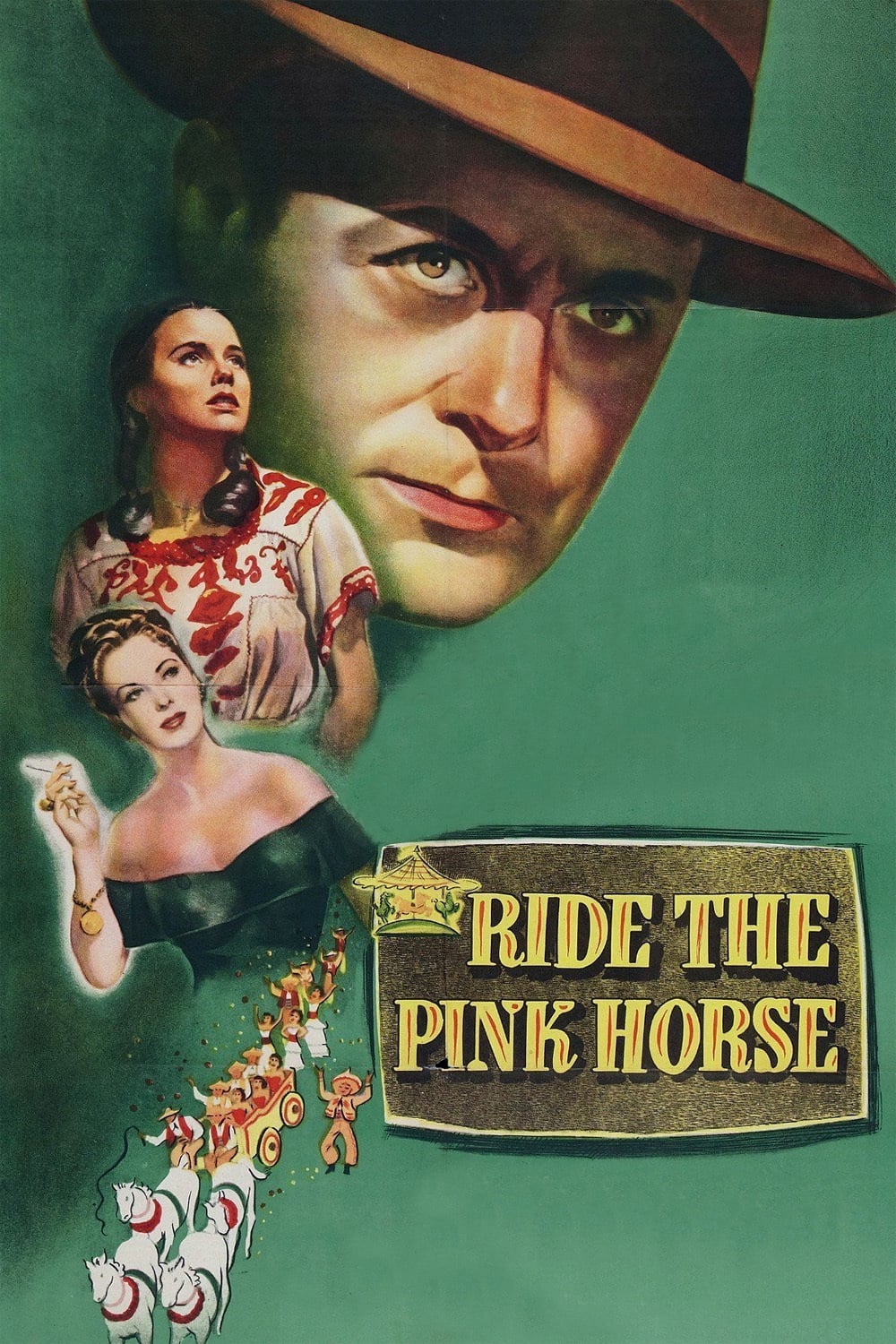

‘Ride the Pink Horse’ (1947)

Robert Montgomery directs and stars as a war vet chasing a payoff in a small New Mexico town during fiesta time. The story comes from a Dorothy B. Hughes novel and keeps her mix of romance and menace. Thomas Gomez stands out as a carousel owner whose kindness changes the balance of power. The setting adds music and crowds that heighten every private deal.

‘Raw Deal’ (1948)

Anthony Mann and cinematographer John Alton make shadows feel like bars in this breakout tale gone wrong. Dennis O’Keefe tries to flee with Claire Trevor while Raymond Burr stalks them from the rear. The first person narration from Trevor adds a bruised intimacy that deepens the desperation. Every frame looks carved from smoke and glass.

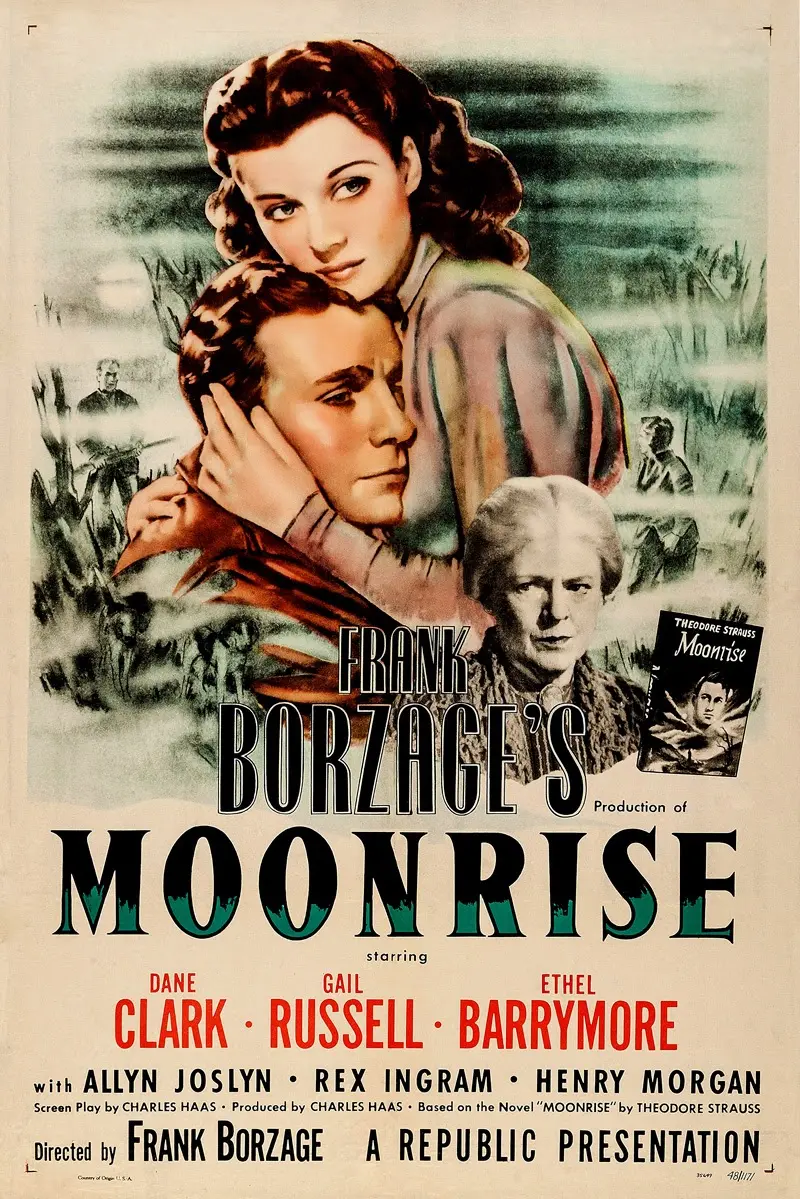

‘Moonrise’ (1948)

Frank Borzage turns a story of guilt into a moody journey toward grace after a killing in a rural community. Dane Clark and Gail Russell give vulnerable performances that pull the drama inward. The production uses sets and fog to paint a psychological landscape around the characters. You can feel how fear loosens its grip as choices become clearer.

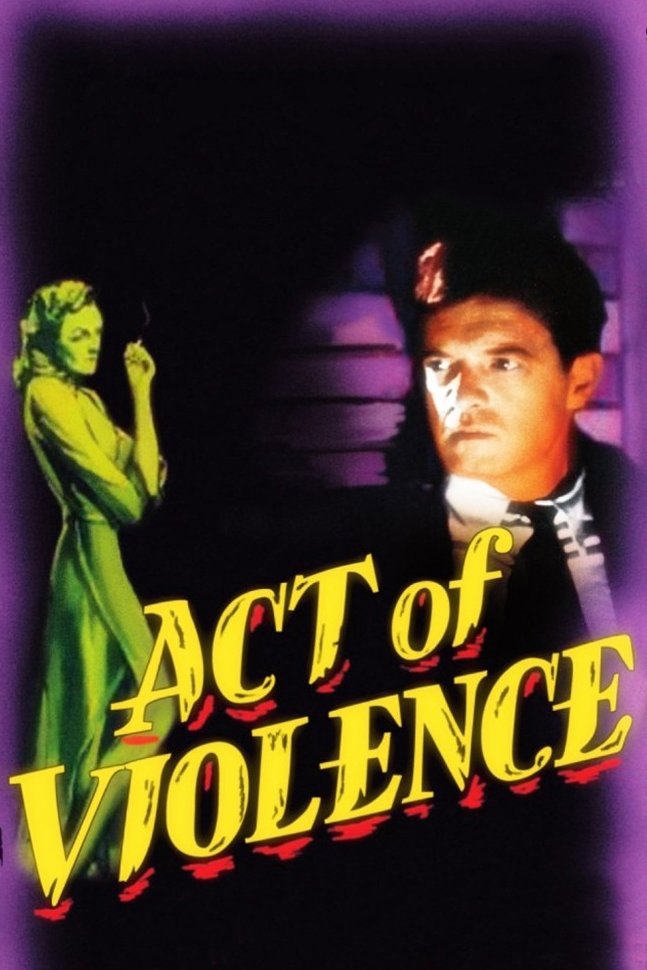

‘Act of Violence’ (1948)

Fred Zinnemann explores postwar trauma when a quiet family man is pursued by a former comrade. Van Heflin and Robert Ryan face off in a moral trap that gets tighter with each encounter. The film moves from tidy suburbs to a bleak downtown world where past deeds never stay buried. Its finale pushes the characters to face what they owe each other.

‘Blast of Silence’ (1961)

Allen Baron directs and stars as a hitman walking cold winter streets while a gravelly voice narrates his fate. The production shot guerrilla style in New York, which gives every corner a raw immediacy. You see diners, subway platforms, and cheap rooms that feel grabbed in the moment. The result is a spare and haunting entry that bridges classic noir and modern grit.

‘A Colt Is My Passport’ (1967)

Takashi Nomura delivers a stylish Japanese noir about a hitman who refuses to run from a double cross. Joe Shishido leads with cool restraint while a jazz tinged score glides over crisp action beats. The story balances quiet planning with sudden confrontations in open lots and docks. Its ending lands with fatal calm that lingers.

‘Le Doulos’ (1962)

Jean Pierre Melville draws a web of thieves and informers where loyalty shifts with every meeting. Jean Paul Belmondo and Serge Reggiani circle each other through interrogations, safe houses, and setups. The camera favors long coats, bare rooms, and watchful faces that hide more than they reveal. The final turns click into place with a cool inevitability.

‘Odd Man Out’ (1947)

Carol Reed follows a wounded fugitive across Belfast as the night tests everyone he meets. James Mason gives a searching performance that mixes resolve with mounting dread. Expressionist touches turn rain and neon into a moral fog around the chase. Each encounter becomes a mirror that reflects what people will do when danger comes close.

‘Union Station’ (1950)

A kidnapping case draws law officers into a tense search that uses a busy rail hub as its beating heart. William Holden and Nancy Olson work across multiple platforms, tunnels, and offices to flush out leads. The film’s tight geography turns timetables and crowds into tools for suspense. Its climactic sting operation uses confined spaces to keep every second sharp.

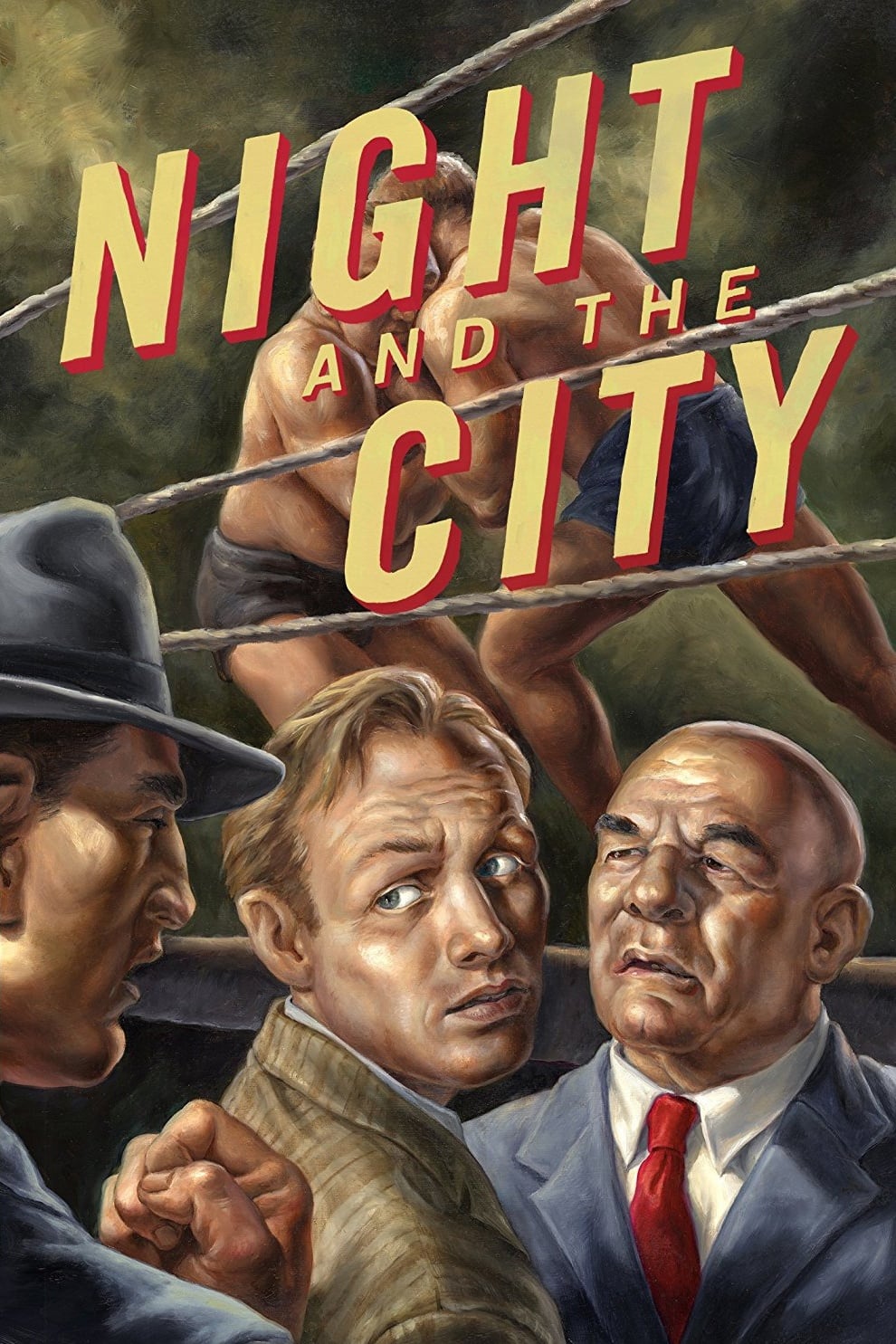

‘Night and the City’ (1950)

Jules Dassin sets a hustler loose in London’s wrestling underworld where one bad bet sinks everything. Richard Widmark drives the pace with schemes that keep slipping through his fingers. The production shoots real streets and cavernous arenas that amplify the character’s desperation. It builds to a chase that feels both inevitable and heartbreaking.

‘Murder by Contract’ (1958)

Irving Lerner follows a careful hitman who treats killing like a business assignment. Vince Edwards moves through Los Angeles with a cold routine that keeps emotions shut out. The production uses spare locations and a cool guitar score that set a clipped rhythm. Later filmmakers cited its clean lines and offbeat tone as a key influence.

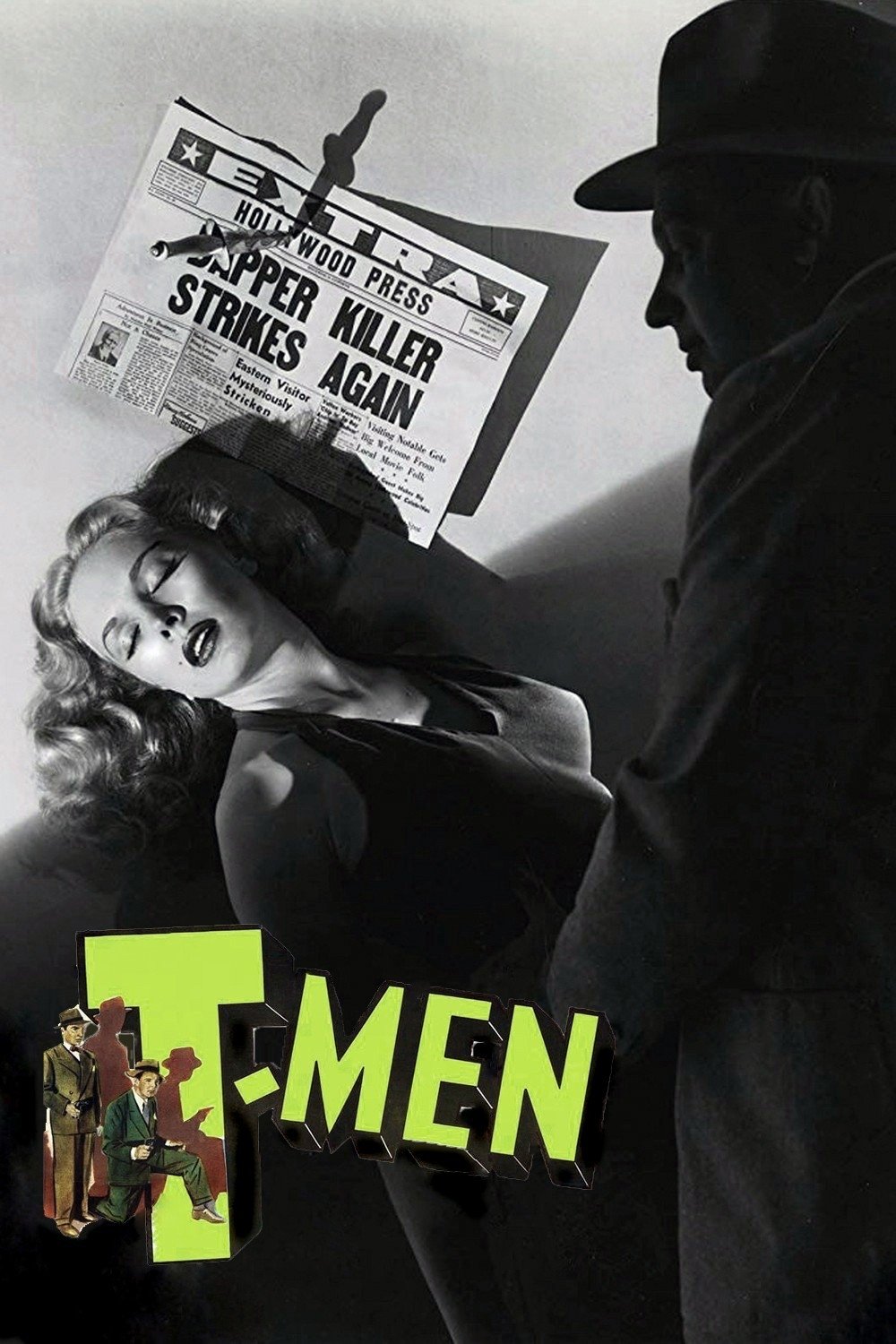

‘T-Men’ (1947)

Anthony Mann stages a deep cover case as two Treasury agents infiltrate a counterfeit ring. The pseudo documentary style opens with official narration and on location detail. John Alton’s lighting turns warehouses and alleys into traps where faces vanish into black. A bathhouse confrontation shows how the operation tests every nerve.

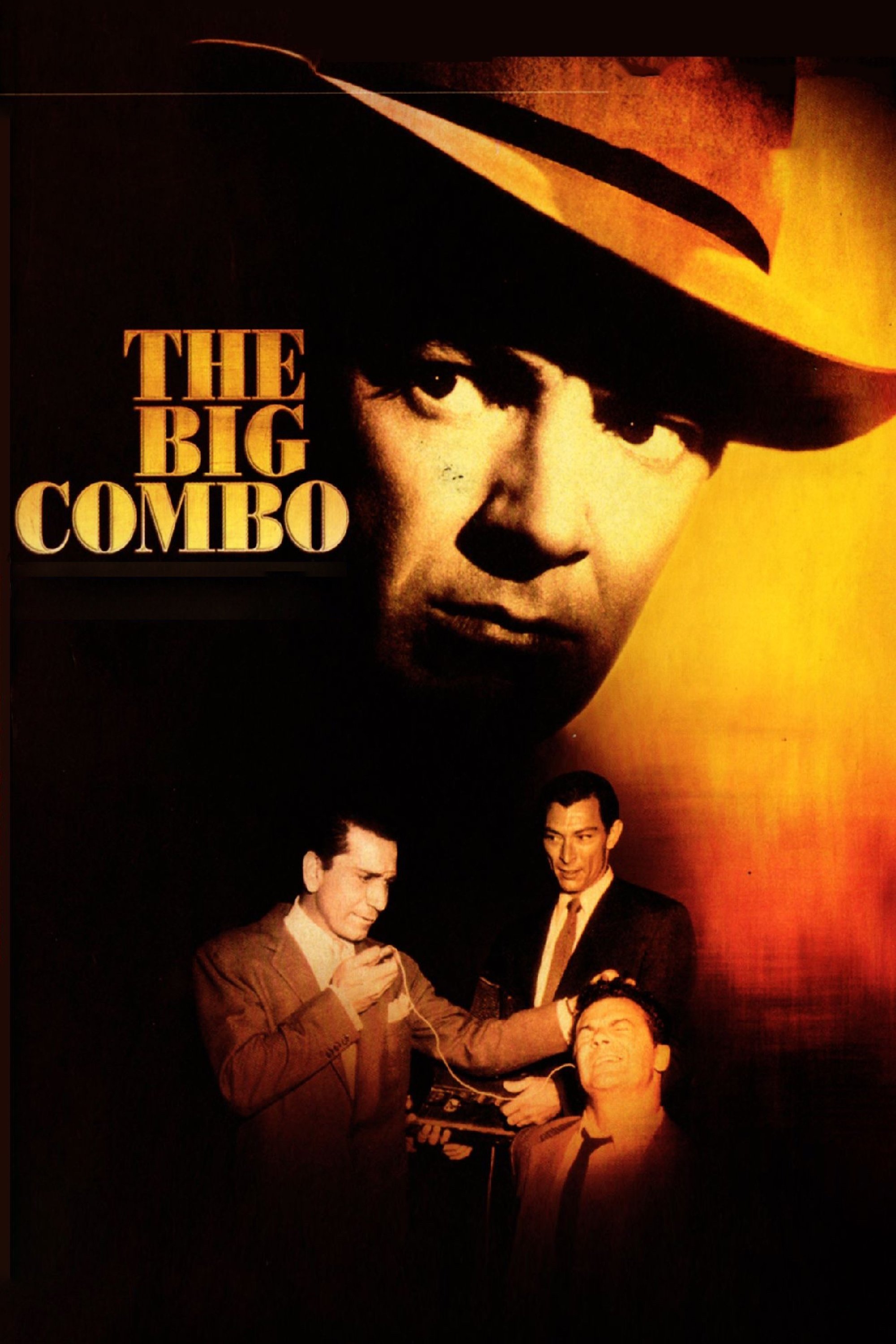

‘The Big Combo’ (1955)

Joseph H. Lewis pits a relentless cop against a suave crime boss who keeps his world airtight. Richard Conte and Cornel Wilde drive a plot built around loyalty and leverage. John Alton shoots long corridors and open rooms that swallow people whole. A hearing aid interrogation scene pins the theme of power to a single cruel sound.

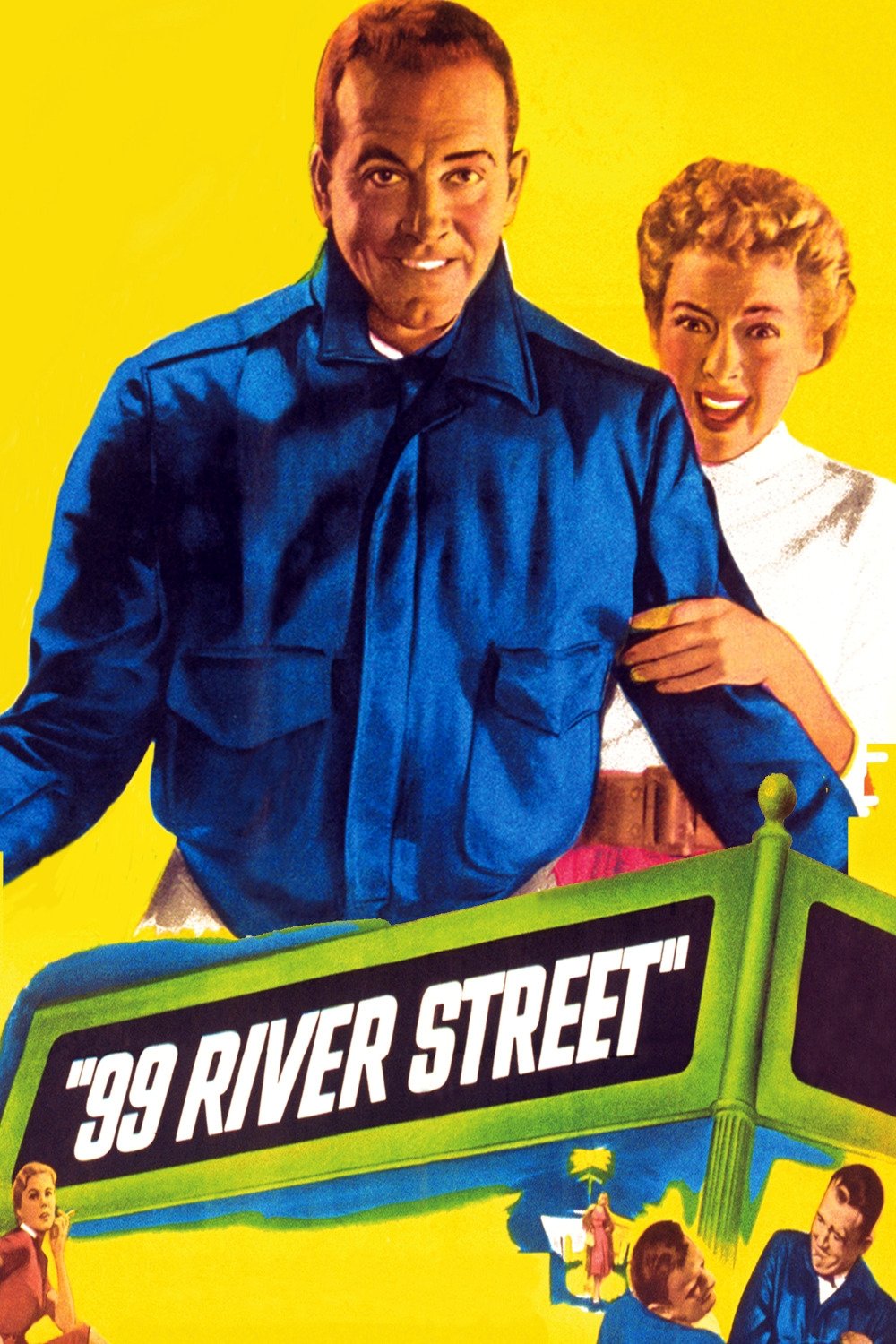

’99 River Street’ (1953)

Phil Karlson centers a former boxer who now drives a cab and gets tied to a robbery and a body. John Payne races through waterfront streets and cramped apartments looking for the piece that clears him. Evelyn Keyes plays an actress whose schemes collide with the case. The story uses rehearsal spaces and docks to keep the chase close to the ground.

‘Hollow Triumph’ (1948)

Paul Henreid produces and stars as a gambler who takes a dangerous shortcut by stealing another man’s face. Joan Bennett becomes the one person who sees through the angles of his new life. John Alton photographs offices and clinics with mirrors that split every frame. The double identity plot turns routine errands into tests of nerve.

‘The Narrow Margin’ (1952)

Richard Fleischer locks a police escort and a mob witness inside a speeding train. Charles McGraw and Marie Windsor trade sharp lines while compartments and corridors shrink by the minute. RKO built tight sets that force close quarters and quick choices. The climax uses shifting cars and doorways to spring a final trick.

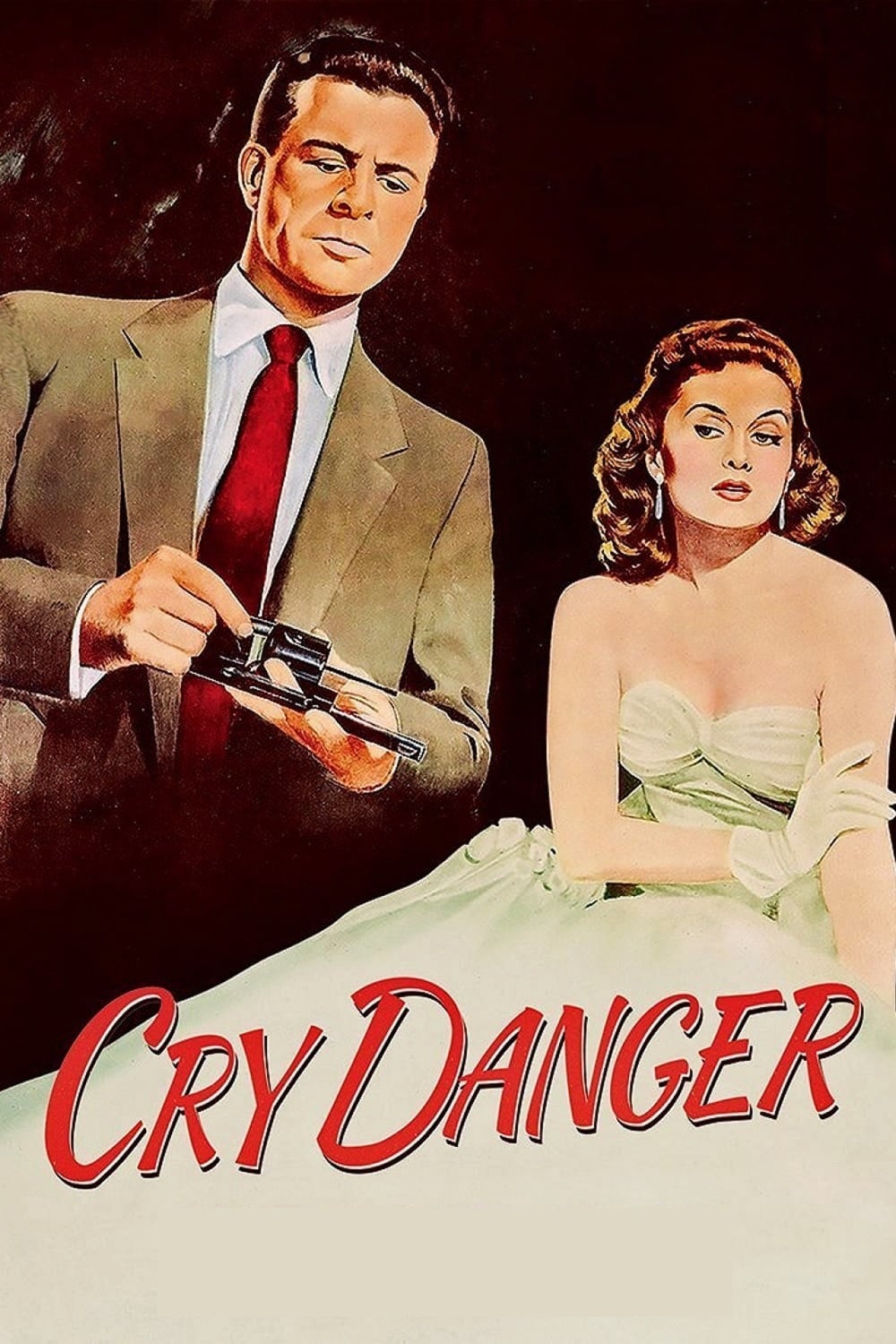

‘Cry Danger’ (1951)

Dick Powell walks out of prison and into the Los Angeles hills to find who set him up. Rhonda Fleming and Raymond Burr anchor a knot of favors and old scores. The production shoots Bunker Hill bars and rooming houses that were vanishing even then. A dry wit runs through the dialogue as the clues tighten.

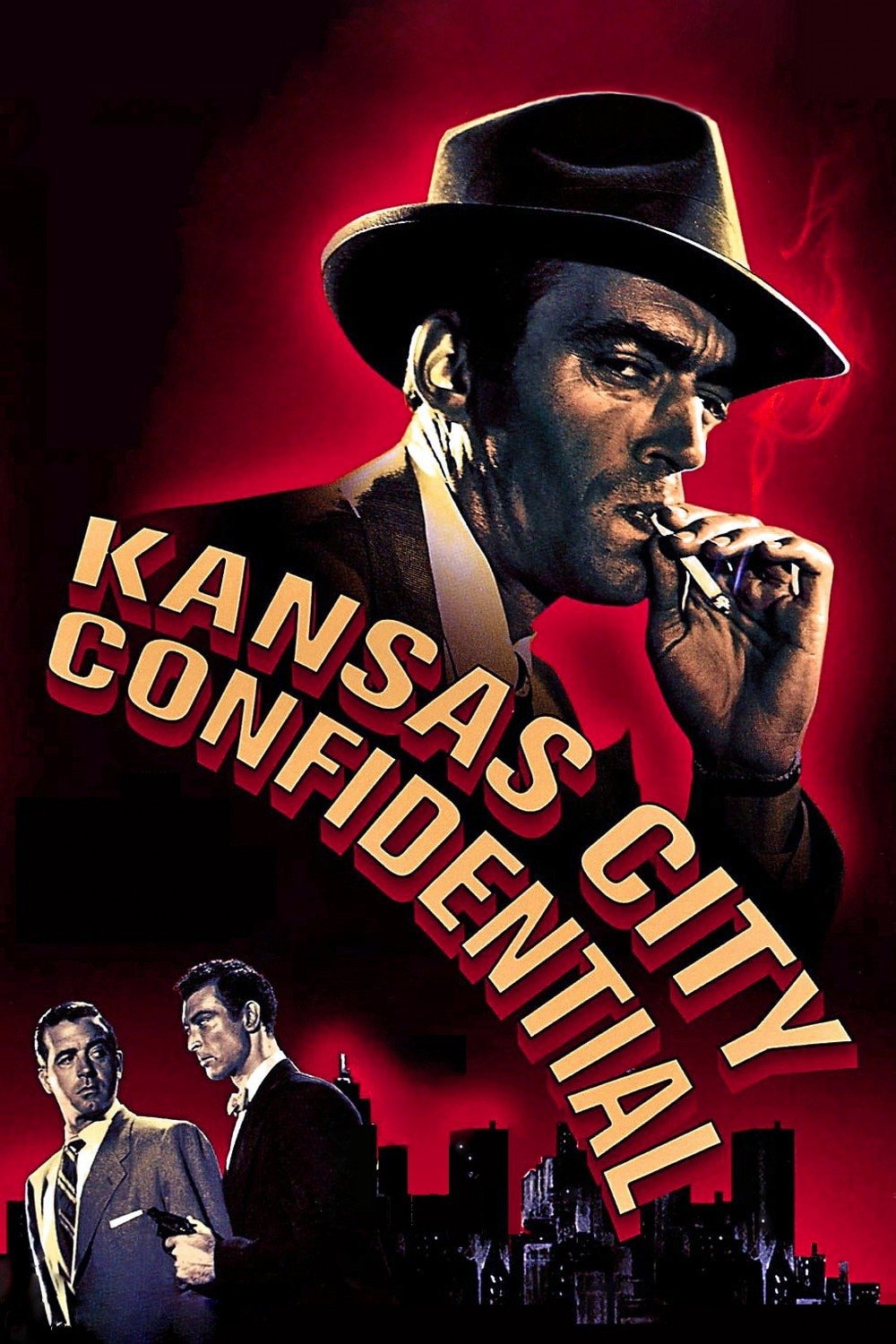

‘Kansas City Confidential’ (1952)

Phil Karlson designs a masked robbery where the crooks never see each other’s faces. John Payne gets blamed and then hunts the team across borders to clear his name. Colleen Gray threads into the plot as family ties blur with suspicion. The setup creates a chain of double crosses that keep identities hidden.

‘Drive a Crooked Road’ (1954)

Mickey Rooney plays a shy mechanic whose racing skills make him the perfect wheelman for a big job. Dianne Foster draws him toward a crew that knows exactly how to bait the hook. Richard Quine directs from a script by Blake Edwards that keeps the plan deceptively simple. Garage bays and cliffside roads become stages for quiet pressure.

‘The Sniper’ (1952)

Edward Dmytryk focuses on a disturbed gunman in San Francisco while detectives track patterns and missed warnings. The film mixes police procedure with scenes of treatment that were rare at the time. Rooftops, stairwells, and streetcars map the hunt in clean lines. A final standoff shows how fear spreads through a city.

‘Cornered’ (1945)

Dick Powell plays a veteran who follows a trail from Europe to Buenos Aires to find a collaborator. Edward Dmytryk builds the search through bars, boarding houses, and political back rooms. The script ties personal revenge to a wider network that keeps shifting shape. Each lead opens a door to another name and another lie.

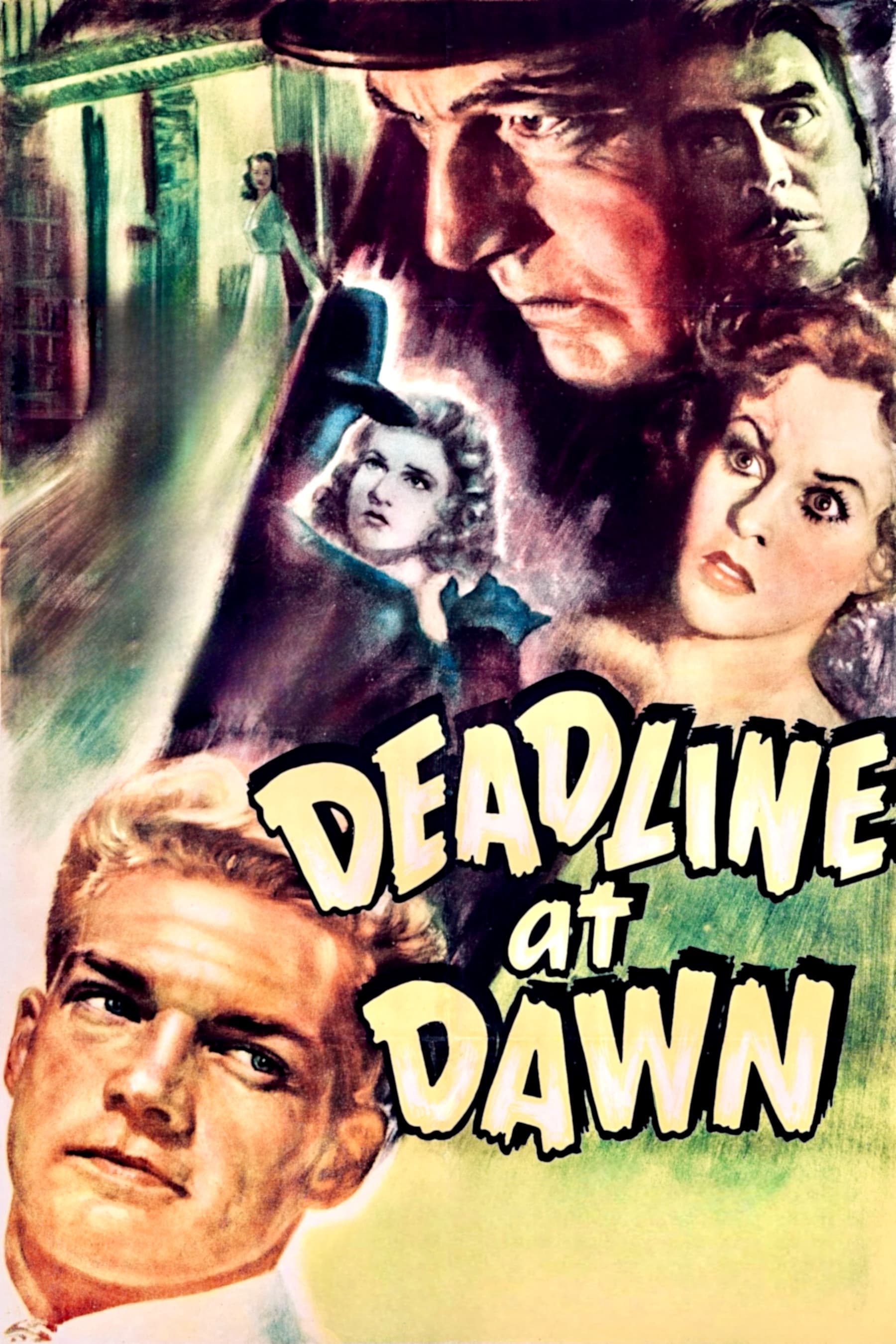

‘Deadline at Dawn’ (1946)

A young sailor and a dance hall hostess spend one long night trying to return money and clear a murder. Harold Clurman directs from a Clifford Odets script that treats the city as a maze of strangers. Diner counters, taxi rides, and rehearsal rooms build a ticking tour of clues. The pair keeps moving because stopping means the police close the door.

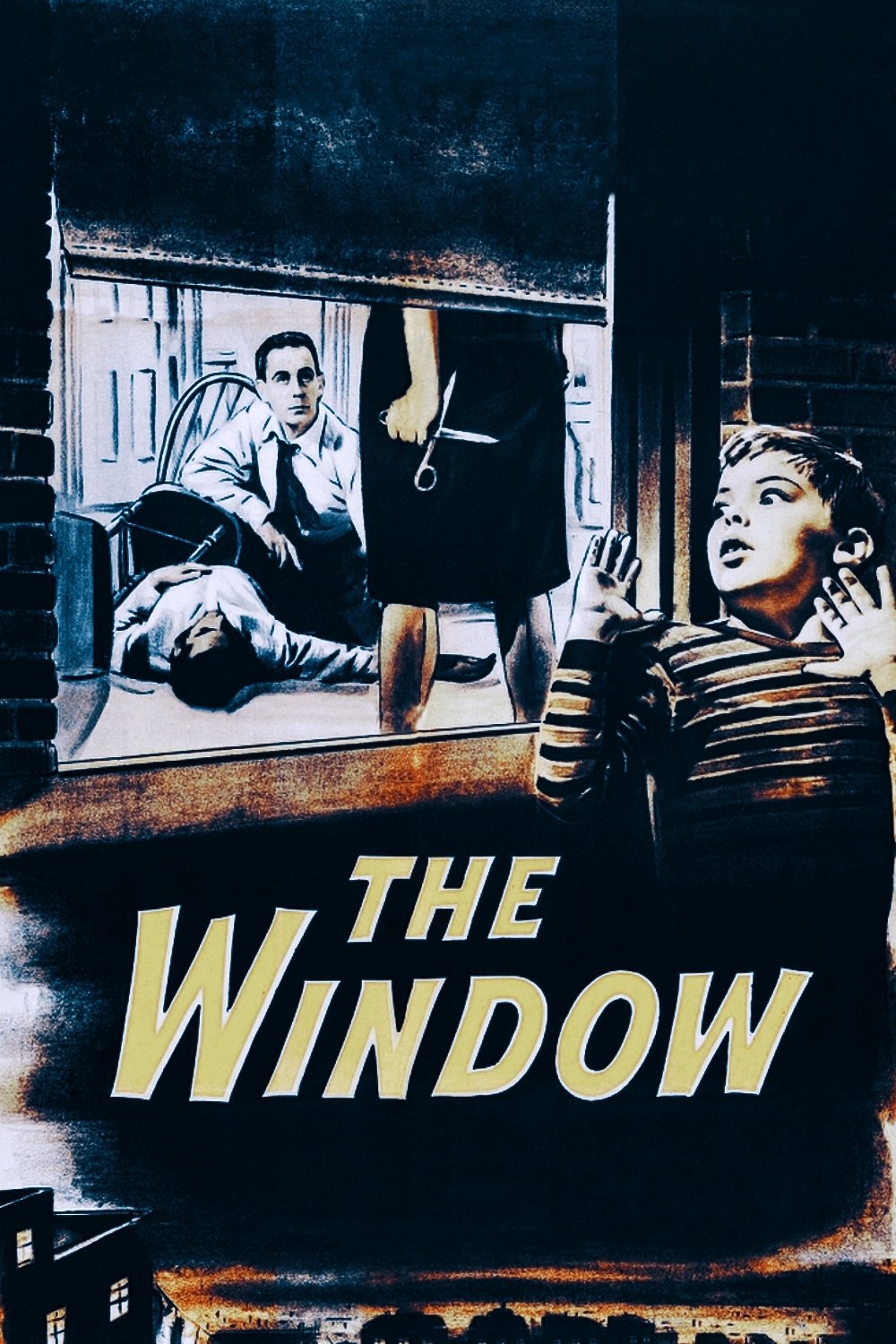

‘The Window’ (1949)

A boy sees a killing from a fire escape and cannot convince adults that danger is real. Ted Tetzlaff uses tenement courtyards, vacant apartments, and narrow stairs to frame the threat. The story comes from Cornell Woolrich and plays on the cost of not being believed. A nighttime chase through beams and scaffolds locks the fear in.

‘The Lineup’ (1958)

Don Siegel follows two killers who collect smuggled contraband hidden in ordinary luggage. Eli Wallach brings a clipped menace as the crew moves through San Francisco’s piers and hotels. The case builds toward a white knuckle pursuit on elevated roads and a waterfront terminal. Police and criminals trace the same map from opposite sides of the city.

‘Pitfall’ (1948)

André de Toth tracks a weary insurance man whose casework entangles him with a client and a volatile private eye. Dick Powell plays the investigator who wants out while Lizabeth Scott becomes the connection that keeps pulling him back. Raymond Burr looms over the story as a heavy who will not let things settle. The film uses suburban rooms and quiet offices to show how danger moves in plain sight.

‘The Dark Corner’ (1946)

Henry Hathaway drops a hard luck private detective into a New York maze of society patrons and hired muscle. Mark Stevens and Lucille Ball work the case from cramped offices to gleaming galleries. Clifton Webb and William Bendix shape the pressure from opposite ends of town. The plotting turns on forged identities and art world cover stories that hide ruthless deals.

‘They Made Me a Fugitive’ (1947)

Brazilian born director Alberto Cavalcanti sets a demobilized airman against a black market gang in postwar London. Trevor Howard hunts through bomb scarred streets and railway yards after a job goes wrong. Sally Gray becomes the one ally who keeps him moving as the net tightens. The film’s grit comes from real locations and a view of petty rackets that feed on hardship.

‘The Long Memory’ (1953)

John Mills plays an ex convict who returns to the Thames marshes to face the people who framed him. Robert Hamer builds the story around foggy riversides, barge moorings, and a derelict hulk used as a hideout. A police inspector tracks the case while the past resurfaces in small, telling details. The script treats revenge and forgiveness as equally costly choices.

‘So Dark the Night’ (1946)

Joseph H. Lewis sends a celebrated Paris detective to a rural village where a romantic retreat turns sinister. Steven Geray follows a trail that links missing persons to a pattern no one wants to admit. The direction favors careful framing and sudden cuts that suggest a mind under strain. A final reveal ties the procedure to a disturbing psychological turn.

‘Decoy’ (1946)

Jack Bernhard spins a pulp plot about a gang moll who manipulates doctors, crooks, and cops to find hidden money. Jean Gillie gives the character a cool focus that drives every scene. The story involves an experimental medicine used to bring a man back long enough to talk. Graveyard rendezvous and motel rooms create a ruthless chain of bargains.

‘The Reckless Moment’ (1949)

Max Ophuls observes a mother who covers up a crime to protect her family and draws a blackmailer to her door. Joan Bennett and James Mason push and pull through letters, phone calls, and ferry crossings. The camera tracks domestic spaces with fluid ease while the screws turn tighter. Businesslike exchanges slowly become personal as the cost of secrecy mounts.

‘Pale Flower’ (1964)

Masahiro Shinoda follows a yakuza gambler just out of prison who meets a thrill seeking woman at an underground card room. Ryō Ikebe and Mariko Kaga circle each other through late night games and street races. Toru Takemitsu’s score adds an unnerving edge that keeps every scene taut. Modernist compositions make neon, alleys, and temples feel equally dangerous.

‘I Am Waiting’ (1957)

Koreyoshi Kurahara opens with a washed up boxer and a nightclub singer who are both stuck in stalled lives. Yūjirō Ishihara plans a way out while keeping clear of local mob interests. The film builds moody waterfront nights with diners, piers, and backrooms that trade favors. Small gestures and half truths become the steps to an escape.

‘Intimidation’ (1960)

Koreyoshi Kurahara pits a bank manager against a blackmailer who knows exactly how the promotion ladder works. The scheme triggers a robbery plan that traps co workers in a strict corporate hierarchy. Tight interiors, barred windows, and safe rooms underline who holds the keys. The fallout shows how status can be used as a weapon.

‘Take Aim at the Police Van’ (1960)

Seijun Suzuki starts with a roadside ambush and then lets a suspended prison guard do his own digging. The search runs through modeling agencies, firing ranges, and smoky clubs linked by a hidden courier route. Offbeat angles and quick cuts keep the mystery off balance by design. The finale pulls together clues that were hiding in plain sight.

‘Cruel Gun Story’ (1964)

Takumi Furukawa stages an armored car job led by a paroled gunman who wants to help his sister. Joe Shishido pulls a crew together for a plan that depends on perfect timing and hard exits. The job goes sideways and forces a series of split second choices on docks and highways. The ending lands with the bleak logic of a closed world.

‘Black Test Car’ (1962)

Yasuzō Masumura turns corporate rivalry into espionage as auto firms steal designs and sabotage test tracks. Hideo Takamatsu’s security chief runs informants while executives trade loyalty for leverage. Boardrooms, motels, and proving grounds become a map of industrial spying. The story treats the showroom as a front for something far more cutthroat.

‘The Small Back Room’ (1949)

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger focus on a bomb disposal expert battling chronic pain and bureaucratic meddling. David Farrar studies booby trapped devices while his relationship with Kathleen Byron strains under the pressure. A sequence on a shingle beach with a ticking weapon remains the centerpiece. The film treats addiction and pride as hazards equal to any fuse.

‘It Always Rains on Sunday’ (1947)

Robert Hamer follows a housewife who hides an escaped convict in her East End home during one crowded day. Googie Withers anchors a story that jumps between market stalls, pubs, and railway arches. Police piece together movements while ordinary routines mask quick decisions. The weather, train schedules, and family obligations keep the clock running on every scene.

Share your favorite overlooked noir in the comments so everyone can discover a few more dark treasures.